Election Act in Estonia fails to define electronic vote, but requires them to be counted. Gaps in regulation have led voting software to invent definitions of its own, resulting the mandate of parliament after 2023 elections being based on invalid ballots.

Despite near equal usage of e-voting and paper ballots in 2023, the results for different voting methods were as from different worlds. There is a huge popular demand to fix the problems with Internet voting, but very little agreement on what do they consist of.

Estonia spouts official and binding electronic elections since 2005 and it has been a controversial yet an interesting journey. The building blocks of initial system have been replaced, but the lure of trusting operational security instead of democratic oversight is still very much there.

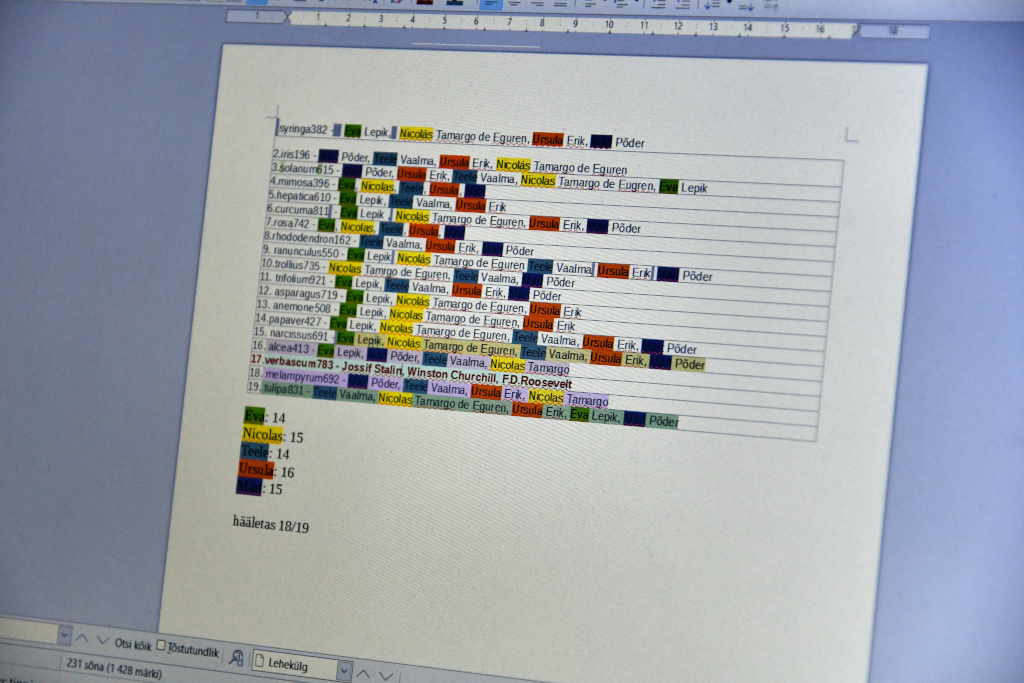

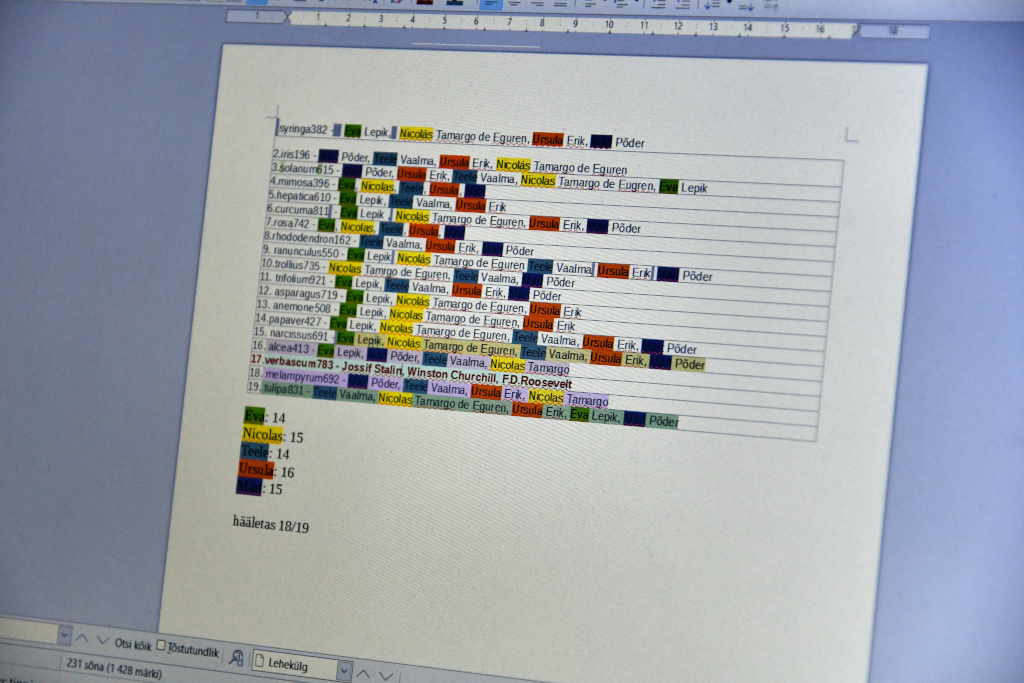

How we conducted a reasonably secret ballot using our digital equivalents of collecting hats and ballot papers and thereby maintained control and trancparency of the democratic process.

I ran for the Parliament in the list of Green Party because they agreed to include in their election platform the Pirate Party program of digital rights in information society. We drafted the program specially for Estonian Parliament elections 2019 and offered it to other political parties too. Although created for 2019 elections the program probably retains its actuality for next half a dozen years least.

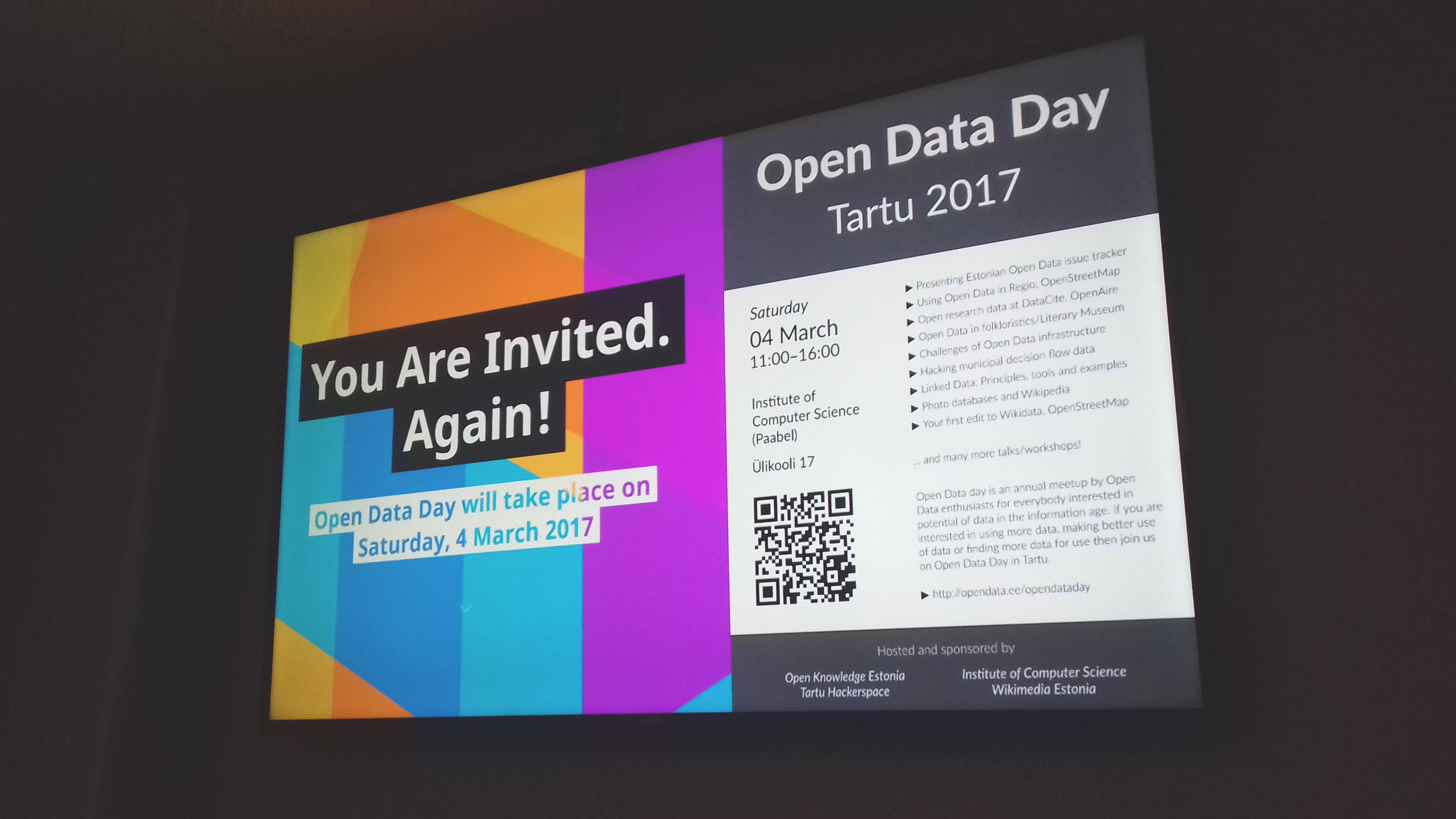

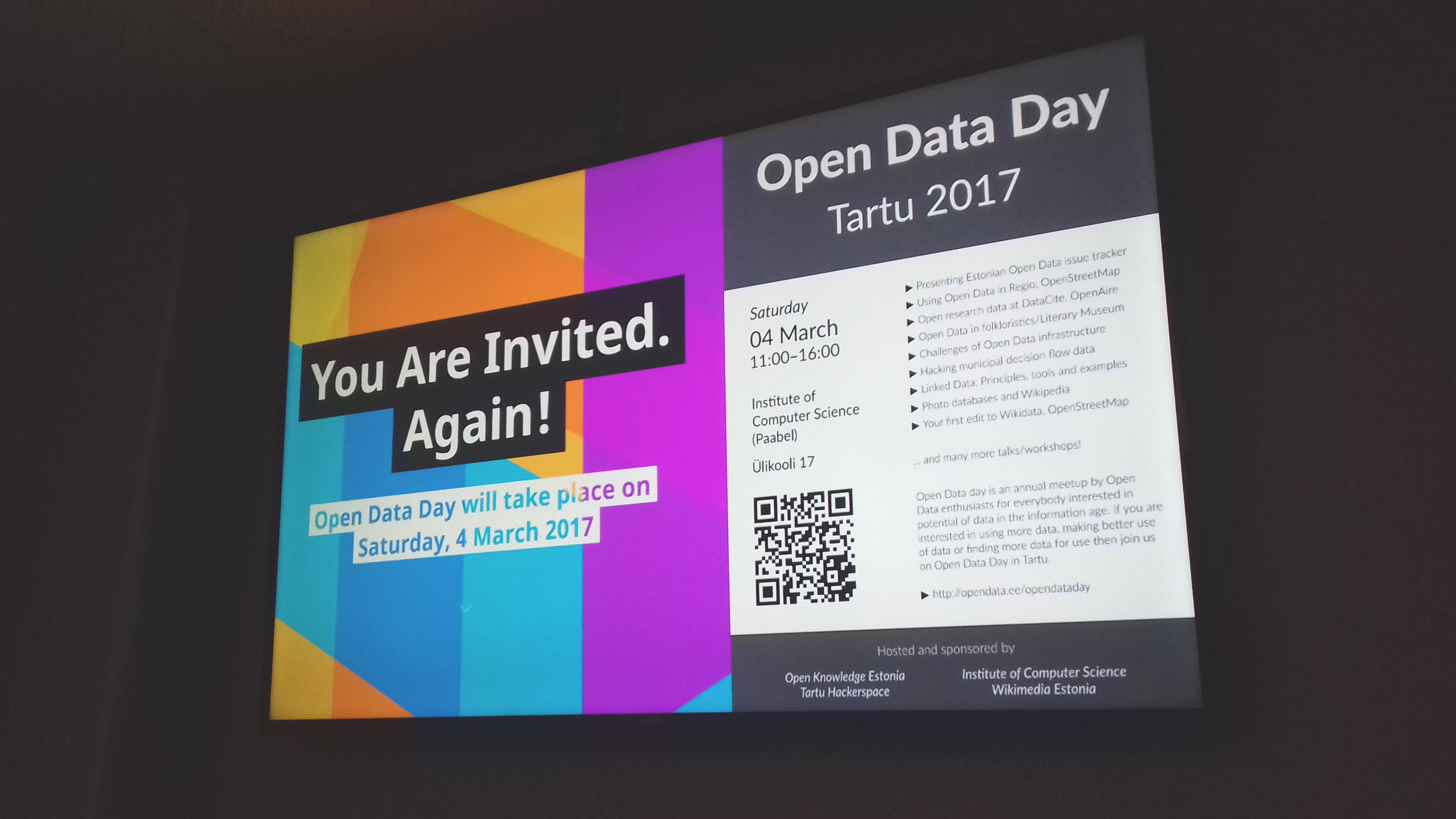

Only days after Estonian Open Knowledge activists organized series of discussions about status and challenges of Open Data reforms in Estonia, where at the house of Chancellor of Justice of Estonia all interested parties were invited to participate in an open discussion, [1] an opportunity that none of the current government officials responsible for the digital issues decided to use, we find them preaching the success of Open Data reforms in Washington.