Votes without ballots: e‑voting at 2023 elections in Estonia

Election Act in Estonia fails to define electronic vote, but requires them to be counted. Gaps in regulation have led voting software to invent definitions of its own, resulting the mandate of parliament after 2023 elections being based on invalid ballots.

In fact none of 312 181 electronic votes counted at 2023 parliament elections conformed to legal requirements and according to Election Act they should have been all declared invalid. Since e-votes made up 51 percent of all votes, this would have drastically changed the election result. Considering the importance of the success story of Internet voting for Estonian public conciousness, it is not completely surprising that none of the institutions from Supreme Court to Prosecutor’s Office was bold enough to address the shortcomings. However, lack of legal explanation on why illegal e-votes were counted and failure to deal with election complaints raises tough questions about the future of Estonia’s e-voting experiment. This is the second part of my observer report documenting and discussing the aftermath of my interventions into 2023 parliament elections in Estonia.

WARNING! This is a draft report that was presented at Chaos Communication Congress in 2023. Since the events covered were not completely finished in 2023, the report was updated later and since the disputes are not over as of 2025, the report is still not formally finished and will probably remain so. The core findings of the report are final though and you can find the summary here.

Avoiding legal definition of electronic vote in Election Act of Estonia is not accidental and has nothing to do with ballots as such disappearing because of an electronic medium. It is rather in service of an idea that electronic voting is much more secure compared to the paper ballots and can not be mistaken because computers are used. If e-voting is essentially error prone, there is no need for detailed legislation or observers, who make sure of the correctness of the procedures and the election results.

Although maybe not always directly admitted, all of that has been suggested by pro e-voting government parties or their officials and much of that has already come awkwardly true during years of Estonia’s Internet enabled elections starting from 2005.

Banishing the ballots

Trying to get rid of ballots arguably brings us back to political debates of 19th century, where in most of the western countries ballots were gradually introduced as a advancement in election technology and a guarantee for free vote. In Estonian case getting rid of ballots manifests the idea that in realm of electronic voting invalid ballots can not possbily exist:

“In case of electronic voting voter makes a choice between candidates in voter application. In comparison to paper ballot elections this rules out possibility of invalid ballots, because voter application is guaranteed to render voter choice into a valid e-vote.” (PS § 60 comment 60)

The pretentious statement from a recognised commented edition of Estonian constitution is mistaken on every level, but proved also wrong in practise alreadly during first hours of 2023 elections. There were candidate lists of a wrong district presented to some of the voters, resulting 63 of them presumably casting invalid votes. The voters were instructed to recast their votes after candidate lists were updated. According to reports 59 of them did recast their votes electronically, one instead chose to vote on paper and three did not react.

Those three remaining presumably invalid votes do not appear in election statistics, because they were removed from ballot box before counting. This was done either because electoral bodies were not sure that the cryptographic tally tool would correctly declare them invalid or to maintain an image that there are no invalid ballots in electronic voting – or both.

This is not just an instance of strange constitutional aversion to invalid ballots, but the organisation of electronic voting in general seems to undermine the principles that ballots have brought to elections.

In the following observer report I am specifically documenting how the attempt to observe ballot procedures including the scrutiny of counting the ballots is systematically failing. Although with partial succes in fighting my way into observing the processes, I was denied any legal recourse among other observers and political parties filing election complaints.

Lack of transparency and accountability is why after 2023 elections observers of various backgrounds and experience gathered to compose a joint statement underlining the need for meaningful observability of electronic voting in five specific demands. This is currently waiting to be processed by the Constitutional Committee of the parliament.

At the same time it has been observed that Intenet voting in Estonia is based on a rather extravagant constitutional interpretation of ballot secrecy, which was preemptively enacted by Supreme Court during intense political debates about introducing the new voting method in 2005. This has resulted in creating vote verification mechanism in 2013 that according to OSCE/ODIHR election experts “contradicts national legislation and international standards pertaining to vote secrecy”.

It appears that electonic voting in Estonia is indeed built on principles that contradict the idea of ballot altogether up to the point of getting rid of secret ballot, that was the main democratic advancement of introducing ballots during 19th century and has been inseparable part of democratic elections since.

Context of the disputes

The complaint about without legal basis removing three presumably invalid votes from electronic ballot box was filed by election observer Sulev Švilponis. Supreme Court commented on it, but unfortunately failed to follow the technical protcol in explaining why it was possible to remove the vote containers before decrypting the part that supposedly represented the wrong district and the candidate, that voter was not eligible to choose.

But even more, it appears that also election software itself failed to follow the technical protocol, because the encrypted data field, that was meant to specify one of the twelve electoral districts recorded 0000 on all electronic votes instead of classificator of administrative units and settlements (EHAK). Supreme Court mistakenly builds their argumentation in points 31-34 of the resolution of 5-23-11 on presumption that EHAK field contains correct codes of administrative units.

There is a reasonable doublt that also Supreme Court has been deliberately mislead by electoral bodies, who provided their comments in the process and probably knew or at least were supposed to know that election software invents its own definitions, protocols and data structures differing from those defined in regulation and official documentation.

Closing out the observers

We are left with impression that electoral bodies must have supposed that noone will find out about missing EHAK codes and invalid signatures of electronic votes, because normally the container files are hidden from voter in the depths of the protocol far behind the user interface. I was able to observe that part of the process only because I wrote my own independent voting application as well as vote verification application, that allowed me to engage in close inspection of the technical protocol and download the actual container files used by the system.

Using my voting application I did eventually cast some irregular ballots and paid extra attention on the exact steps of how the vote containers are processed. My goal was to find out which of my recurring ballots will be counted and if processes specified in the Election Act are followed correctly. But irregularities appeared and starting from second tally on 6th of March I was denied from all attempts to get an overview of the procedures which involved processing vote containters and removing invalid ballots.

The initial promises of either providing observers with videos or technical logs of the procedures were not kept and instructions given to submit personal data requests to find out about the procedures related to containers were denied in the end. About a week after the election it started to appear to the observers, that they are deliberately kept away from finding out about the details of processes. This explains why electoral bodies first systematically delayed and in the end denied the information requests of the observers, causing election complaints to either be premature in content or pass the three day deadline.

Although this behaviour was documented and explained in several election complaints Supreme Court did not find a reason to reinstate the deadlines to discuss the problems. The intensity of internal debates of the court however resurfaces in concurring opinion of Chief Justice Villu Kõve of case 5-23-20, where pointing out the limited capability of court to assess complicated technical issues in short timeframe of election complaints Chief Justice goes as far as stating that he expected initiating constitutional review process at least concerning roles of electoral bodies and maybe also the whole complaints process as such. Chief Justice came back to this topic while commenting his annual report to the parliament and explained his position in simple words:

“It would be correct for the Electoral Committee and the Electoral Office to respond to the allegations that the appellants have made. There have been very specific technical claims that were largely dismissed because the appeals were not timely. To prevent these questions from being asked later, they should be answered. The Electoral Committee and the Electoral Office must refute the statements presented to them with arguments, and not fail to respond to them. In my opinion, their communication so far has not been successful and has not removed doubts in the eyes of the public in a sufficiently understandable way. Electronic election cannot be based on faith alone.”

Method of responsible intervention

Lack of cooperation from electoral bodies called for extending the repertoire of usually passive election observers and gave birth to concept of participative election observation, where observer at the same time being a voter uses all the technical, organisational and legal means available to gain meaningful insight into election processes.

The technical tools to engage in close inspection of casting and verifying e-votes are documented in more detailed manner below, but also sharing information received and coordinating queries and complaints between the observers was made use of. Since electoral bodies were deciding matters of observing in ad hoc, even unsuccessful attempts to observe different parts of the system gave information about the processes. Sharing information with political parties contesting electronic voting was also useful and using social engineering to join meeting between State Electoral Office and Conservative People’s Party helped to pressure electoral office to hold a private vote processing session to inspect the e-vote containers submitted to collecting service by me as observer, citizen and a voter.

This method of observation that at times could be rather described as intervention was not carefully planned or premeditated, but quite organically grew out from experience of previous election observation episodes, altmosphere of discussing aspects of electronic voting in Estonia and a decision to join official observer program of 2023 elections from the very start. Possible conflicts of interests and deviations from the role as an observer were mitigated with publicly disclosing all the information as early as possible.

Because of the participative manner of observation the following report does not only formally present the findings, but also explains the legal and technical context of obtaining the information and motivation behind it. Since the findings are parts of processes some of which have still not finished, they are presented in form of episodes following the order of events as they appeared during observation and according to their relative significance and implications for next steps.

The initial report was written during the Election Day and was meant to be a preliminary report expressing the basic presumptions and expectations before vote counting ceremony on the 5th of March. During next week the report was edited for clarity, some mistakes and ambiguities were corrected and illustrations added. The comments framing the report in the context of aftermath were added and some editing was done also during the week after.

The second part you are currently reading is meant to be the final report describing the observer experience and findings for general audience in objective and self sufficient manner. The reader is expected to have some knowledge of electoral processes and electronic voting systems, but most of the prologue and discussion is well understood without deeper knowledge in these matters. The initial report might be consulted to gain better ingsight to the observation process as it actually happened, but is not needed to understand the core content of the final report.

In the following a bit more formal description of the voting system properties relevant to this report is given before presenting the episodes. Already episode 6 about the nature of procedural safeguars, but more specifically the last part discusses the implications of the findings and the experience of the observation as well as speculates on the future developments of e-voting in Estonia.

Properties of the voting system

In Estonia electoral processes are conducted under two electoral authorities. State Electoral Office (SEO) is the structural unit of parliament responsible in conducting the elections under oversight of National Electoral Committee (NEC), that processes the election complaints. Decisions of NEC can be appealed to Supreme Court which is meant to provide ultimate oversight of electoral processes.

In order to ensure that the election results are announced in reasonable interval of time, complaints have short deadlines of three days from the contested legal procedure, the appeals need to be processed in additional 10 days. Legally, NEC should not announce the results before all election complaints that could affect the results are solved. In addition to fast lane election complaints there are offences against election freedom described in Penal Code §160-168, which can be used to report serious offences also months or even years after the election results have been announced and the actual ballots destroyed.

Internet voting

Estonia uses Internet voting, that is available to all voters with government provided digital ID. To communicate with vote collection servers and cast a vote electronically, voters are instructed to download a special voting application and vote verification application, if they want to perform a check if their vote has been actually recorded at the server. As electronic vote needs to be digitally signed, voters need to use a special smart card reader or another digital ID, that has been derived from national identity card.

The IVXV protocol used for Internet voting is created by Cybernetica/Smartmatic, who is also author of the software implementing the protocol. The election servers and supporting infrastructure are run by Information System Authority (RIA).

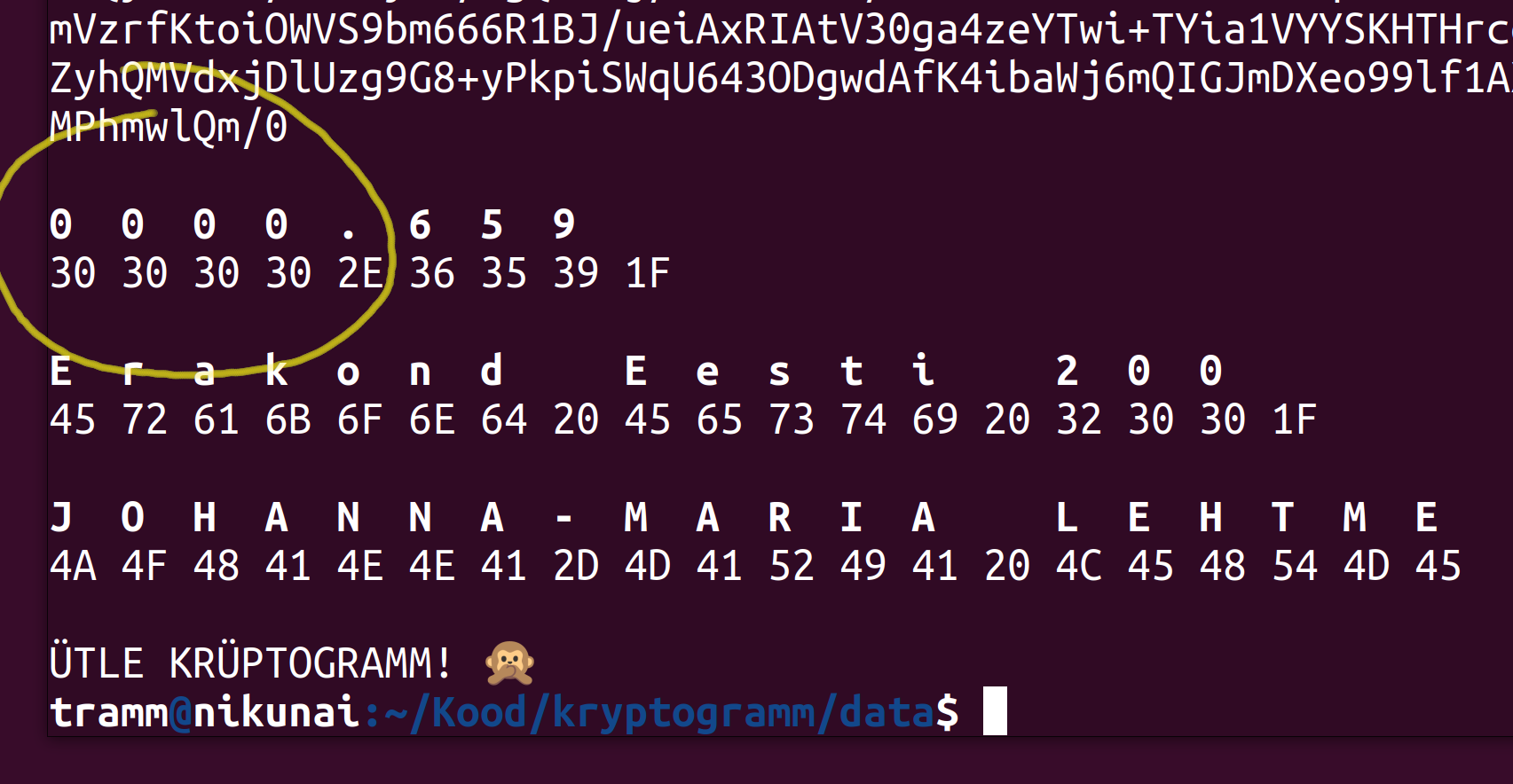

Vote itself is formatted as a binary padded text file containing four data fields, that for 2023 parliament elections had to consist of 1) code of adminisrative unit (EHAK), 2) registration number of the candidate, 3) party affiliation, 4) candidate name. Data fields are appropriately filled and vote text is encrypted using public part of ElGamal key pair of NEC, that is generated before the election. The encrypted vote text is placed in ASiC-E LT container instantiating BDOC 2.1 standard and signed with digital ID.

Encrypted and digitally signed votes are sent to vote collecting service, that stores them until the end of e-voting period, which for 2023 parliament elections started 27.02 at 9:00 and ended 4.03 at 20:00, a day before official Election Day on 5th of March. Voters can recast their votes anytime during the election either electronically or on paper. Voting on paper always overrides an electronic vote and is also available on Election Day, when electronic voting is not provided. Recasting one’s vote is meant as a remedy for the situation where voter has been forced to vote for a candidate agaist their will and overriding the vote on paper is a final way out for the e-voter if problems occur.

The collecting service stores the vote and registers it in a separate registration service, returning the 1) registration receipt with a timestamp and 2) receipt for certificate validation check for digital ID used to sign the vote as well as 3) a vote identification number. Identification number is be used to download the vote from verification service up to three times and up to 30 minutes after casting the vote. Voter can use it to verify that the content of the vote corresponds to what was written in padded text file by decrypting the downloaded cryptogram using ElGamal public key and ephemeral key that was used for the randomness during encryption.

Although the technical protocols for elections are public and anybody is welcome to create their own implementations of election software, electoral bodies encourage casting and verifing votes with the official applications. Voting application distributed by SEO is a closed source binary application for Windows, Linux and Mac systems, that implements casting the votes and submitting them to the collecting server. After casting the vote, a QR code containing vote identification number and ElGamal ephemeral key is displayed by voting application and can be scanned by vote verification application installed on separate Android or iPhone device. Vote verification application downloads digitally signed vote cryptogram from verification service and decrypts it using SEO/NEC public key and ephemeral key, in plain text displaying candidate name and number selected by the voter.

Processing of the digitally signed and encrypted votes starts after 20:00 on Election Day when polling stations have been closed. Procedures start with checking the integrity of the electronic ballot box and removing ballots overriden by recasted electronic votes. For each voter only an electronic vote with the latest timestamp is kept in the ballot box. After that electronic ballots overriden by paper ballots are removed by using cancellation lists based on voter data from polling stations. Votes remaining in the electronic ballot box are then separated from digital signatures by only keeping encrypted text files which are then shuffled using a cryptographical mixnet to ensure that indentities of voters of now anonymised ballots are not traceable in ballot box.

Votes are decrypted and counted on a separate computer using SEO/NEC private key split between its members, requiring five of overall eight to be present to start decryption. Electronic ballot box with all of its copies as well as anonymised votes and SEO/NEC private keys are physically destroyed after election complaints have been resolved and election results announced.

Possibilities for observation

According to the Election Act the results for paper ballots and elecronic votes are both determined in public manner in the presence of the observers. In addition SEO contracts an information systems auditor, who rather formally makes sure that the procedures follow steps specified in laws and regulations and that electronic ballot box and computer systems in certain phases of operation exhibit properties described in technical documentation. This is mostly done by visually observing the procedures, recording checksums of data transferred between parts of the system and in addition using security tape against tampering of the equipment. The auditor also expected to verify converting, shuffling, decrypting and counting of anonymised vote cryptograms using official audit tools.

Observing and auditing are both rather limited and provide only some insight into procedures conducted starting from the SEO/NEC key pair generation to physically destroying the decryption keys and the vote storage media after elections. For example there is no independent oversight over vote collection during six day period and no auditing of vote processing, where repeat votes, duplicate votes, annulled votes and some of the invalid votes are removed. Compared to observers the auditor is in a somewhat better position to scrutinise parts of the process that they are legally required to report on, but is not actively checking for any anomalies in practise.

From 2019 on, altoghether four elections the company contracted for auditing has been KPMG and in 2022 they also conducted a general audit of electronic voting system that the new government used to bury 2019 report of ministerial working group that suggested various tehcnical, legal and organisational improvements to e-voting system. Even if KPMG formally might have no conflict of interest here, in practise they are not really expected to engage in critical scrutiny of the system they declared “electoral systems and the processes sufficiently secure to ensure correctness of e-voting procedures and the election results” in their previous report less than year ago.

Therefore the critical scrutiny of the system can be expected either from international observers like those from OSCE/ODIHR election observation missions or independent observers from Estonia, who also make use of legal means available to them to contest the irregularities discovered.

Tools to extend the observability

The idea of writing an independent voting application has been suggested during discussions about electronic voting for about a decade at least and the first one was implemented, documented and publicly tested by team close to the developers of official e-voting software during 2020-2021. Cybernetica/Smartmatic responsible for the e-voting software have been mildly encouraging independent experiments in that direction for example by providing access to their test servers already in 2017. Also my own experiment of publicly casting an invalid ballot in 2015 preceded with an attempt to communicate with voting servers using command line tools and basic inspection of the source code of voting servers, that was published after public demands in 2013.

Individual vote verification

Invididual vote verification tool Kryptogramm is a command line tool consisting of 250 lines of Python code, that handles decoding the vote identification number and vote encryption ephemeral key from QR code presented for vote verification, downloading the digitally signed vote container and saving it for later use, exctracting the encrypted vote cryptogram from the container and decrypting it using ephemeral key and public key of SEO/NEC. The final result of this is a decrypted vote with its four data fields specifying the administrative unit, candidate number, the party list and the full name of the candidate.

Tool was created publicly during first two days of Election Week, being announced in an interview to national broadcaster ERR on 27th of February (from ~4:00), source code published on 1st of March on GitHub and the motivation publicly documented in an opinion piece on ERR news portal on the following day. The initial motivation of creating the tool was to demonstrate how much effort does it take to create basic mechanism of selling vote cryptograms in black market, that was in 2019 described to Chancellor of Justice and ministerial working group to improve e-voting (cf “Black market for voter cryptograms” in preliminary report).

Custom voting application

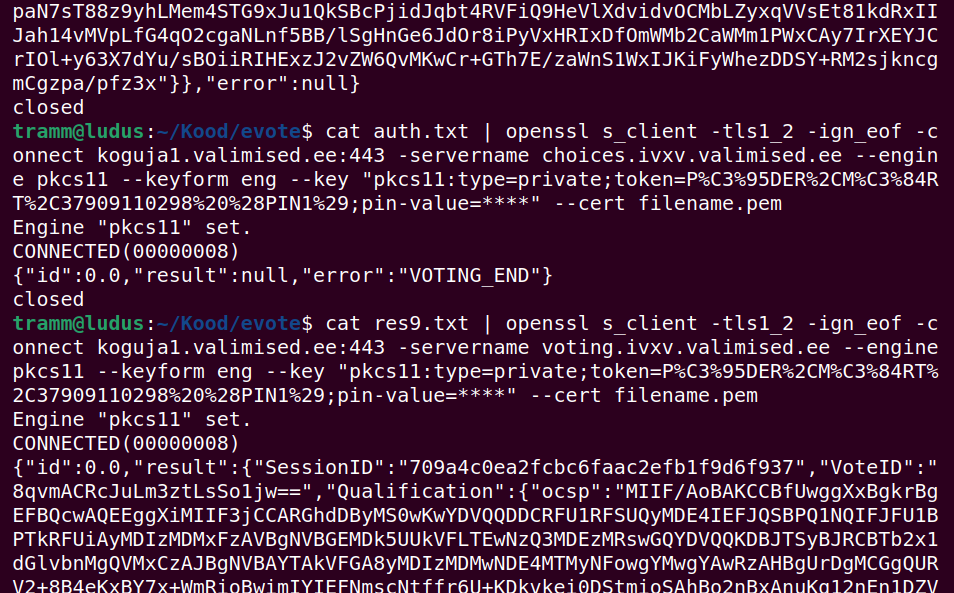

Voting application prototype is a series of scripts and command line tools to compose, encrypt, sign and submit electronic vote containers to vote collection servers.

The prototype uses openssl command line utility configured to use PKCS #11 engine to create an authenticated TLS 1.2 connection to vote collection servers. The connection is authenticated by Estonian ID card and SNI extension is used to request dedicated microservice for receiving candidate list for a voter and submitting the vote container. Python code is used to encode the four data fields and encrypt the resulting plain text using SEO/NEC public key and ephemeral key generated for randomness. The resulting vote cryptogram is placed in an ASiC-E LT container and digitally signed using official digidoc-tool command line utility and Digidoc4 desktop application.

openssl command line tool and inspecting the responses from server in terminal.

JSON-RPC protocol is used to communicate with the collection service and the two expected procedures of retrieving list of candidates and submitting signed vote to storage are implemented by replacing placeholders in simple JSON-RPC formatted text templates and feeding the resulting text files to openssl utility accordingly.

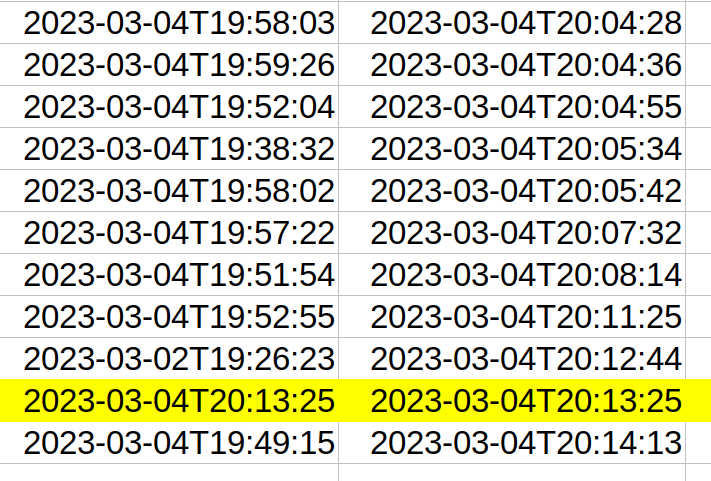

The prototype or rather proof of concept of the voting application was composed during last four hours of e-voting on 4th of March without much looking back, because couple of previous attempts to use Python libraries as well as curl to establish authenticated TLS 1.2 connection to voting server failed and possibility of using openssl was discovered as a last attempt. This is why the first proper DIY vote was submitted to collection server 19:58 which is just two minutes before end of e-voting and resulted in accidentally submitting another vote in 20:13, when electronic voting was already closed.

Access to test server of Cybernetica/Smartmatic was asked and received couple of days before election, but was mostly used to figure out the nuances of the protocol in comparison to interacting with the official election servers. Hints and encouragement from members of Tartu Häkkerikoda as well as helpful people on Internet were also sine qua non.

Episodes

The observers of electronic voting in 2023 parliamentary elections were instructed to participate in training sessions from 14th to 16th February and first observation round on 15th and 16th of February, second on 5th of March and third on 6th of March and fourth of destroying of the votes on a later date. I participated in all the sessions except the vote processing session on afternoon of 5th of March, which was explained to not have anything to do with counting of the votes, and the last round of destroying the votes, date of which was not announced to observers by e-mail as the rest of the procedures. All the training sessions and preliminary observation rounds were participated virtually by making use of Microsoft Teams, during official vote counting sessions of 5th and 6th of March I was present physically.

The general atmosphere of the training sessions was more of SEO conducting their internal procedures and allowing observers to ask questions about it. This is also evident from the fact that the training sessions of 15th and 16th coincided with observation rounds. There was no special learning program planned for the training, initial restriction that the training is Estonian only was changed on first session, where explanations were also given in English. Since questions and answers section transformed quickly into debate between SEO representatives and some of the more experienced observers, this could not have been particularly useful from the viewpoint of instructing new observers. There was also no schedule for training and no dedicated learning materials were delivered, omitting even reference to election handbook for 2023 parliamentary elections.

During the first training session on 14th of February the promise was given that recordings of the observation rounds not containing personal data will be shared with the observers. This promise was not kept, which became especially critical for reconstructing events of vote processing session of March 5th starting at 15:00, because according to Election Act 60¹ section 1 ascertaining of the results of electronic voting was to start not earlier than 20:00, when polling stations were closed. Not many observers participated in that informal/illegal afternoon session or weren’t able to participate because of low quality of the stream and similar technical reasons.

During the first session also the promise was given to respond to personal data queries by voters to let them make sure whether in election the electronic or the paper ballot vote was counted, because the latter will always override the electronic vote. This promise was kept.

I used the first session to request up to date e-voting handbook instead of version 6.0 from 2019 that was still presented at valimised.ee documentation section, request source code of election software to be uploaded and request fixing the documentation concerning vote verification which explained the process according to outdated 2013 protocol. The manual was updated to version 7.0 from February 2023 during next days, the source code was published on 24th of February only three days before the start of e-voting. After repeated requests also the directly misleading parts of the description of vote verification protocol were removed from the web page of electoral authorities for the beginning of the Election Week.

The experience of the first introductionary training session was sketchy, but still meaningful. This however did not last for the second training session of 15th of February that at the same time was the first round of observation.

1. Inspecting the system for malware not possible

According to handbook of electronic voting chapter 2.3 generating the key pair for the election is an audited procedure, for which the auditors and observers are provided means to make sure that key generation system does not contain malware.

Absense of malware could be ensured by rigorous initialisation procedures and affirmed by thorough inspection of the system, but neither of those was pursued and SEO was not able to meaningfully interpret the requirement as described in the handbook.

Although during first observation round on 15th of February the initial question about the setup of the system for key generation was answered, the SEO not only refrained from answering the second question about what means are provided to make sure that the system does not contain malware, but pretended the question was not asked and failed to comment on proposal to make a copy of system disk for later inspection. Since this was supposed to be at the same time a training session, it is even more peculiar that the situation was not commented in questions and answers section after the key generation.

The comment was given during the 16th of February questions and answers session by SEO head Arne Koitmäe in response to coming back to the issue and asking why the requests for clarification by observer were ignored on the previous day. Explanation was that SEO was busy and could not answer and what is meant in handbook is that observers can by visually inspecting the hardware and procedures make sure that there is no malware in key generation system. Since the disk image used to initialise the system was neither registered nor its checksums written down, this did not meet any standard of auditing and observing, that was required by the handbook.

Failure to provide means to make sure the central security measure of the system is not manipulated by malware resulted in an election complaint and NEC decision no 54 that observer shall be provided a way do inspect some of the hard disk images used in the process. According to decision no 54 this was supposed to happen before destroying of the votes on 12th of May, but as in months immediately following elections both the observers and electoral bodies were busy with other issues described in episodes 2-6, the session to inspect the hard disk image in fact took place on 28th of November after summer vacations and occasional attempts to fit the event in schedules from both sides.

In that session the observer was explained that the disk image to be demonstrated was downloaded from MSDN following all the best practises of calclulating and inspecting the checksums, but when the disk was plugged to a computer and booted the operating system, it appeared to have user software installed, among them Notepad++ and Digidoc tool used to work with Estonian digital signatures. There were no checksums recorded for neither the operating system nor user software.

As the system disk created from that image was used for both generating the SEO/NEC key pair for the election and later using the generated private key to decrypt the encrypted ballots from processed ballot box and count them, this would have been a perfect target for anyone who wanted to manipulate the election results. Since the procedures to create the disk image and the actual disk used were neither recorded nor audited, there is no reasonable way even the electoral authority can be sure there was no malware present, that could infere either in key generation or decrypting and vote counting processes.

Generating the SEO/NEC key pair for the encryption procedures and counting of the votes are crucial parts of the election. It is not possible to state that voting results were determined correctly, if integrity of essential parts of the system can not be guaranteed even for the electoral bodies themselves.

KPMG auditors in their report do not explain if or how they fulfilled the requirement to audit that key generation system does not contain malware as specified in the handbook.

2. Containers of e-votes processed in the wrong order

The second episode is related to e-votes submitted using a custom voting application. This enabled to submit a vote after election was over and encrypt the vote without encoding parameters needed to properly decrypt it.

This episode has legal part of refusing to count my personal vote, for which SEO used factually incorrect claims about voter sessions and authentication. NEC on their part claimed that I am a hostile agent and refused to process my complaint and count my vote based on that assessment. As a result my actual vote in 2023 parliamentary election was not counted.

But there is also a technical part about what would have happened, if the electoral authorities would have acted according to the law and tried to properly count my vote.

Failure to remove an after hours e-vote

This part mirrors the problem with 63 invalid ballots, of which four were not recast and for which ad hoc annulment list was created. This had no legal basis and probably was also illegal in content, but it would have been legal to remove from ballot box the vote received at 20:13, when e-voting was already over. This would have indeed started a regression and problem with processing the containers in wrong order should have been solved, but this would have shown the ability of electoral bodies to actually conduct e-voting according to the law.

The gist of the fist part of this episode is SEO failing to count an electronic vote created by independent voting application and instead retaining the container received on 4th of March at 20:13 after the end of e-voting period. A valid electronic vote was not detected in the container and it was declared an invalid vote (presumably the “invalid e-ballot canceled” of KPMG’s 13.03.2023 interim report refers to the same container/ballot declared invalid, see Interim Report page 4).

During submitting the vote at 20:13 the voting server responded with "error":"VOTING_END", which gave a clear indication that the vote was not accepted. NEC explanation in decision no 75 of 17.03.2023 fails to state correct facts about what happened during voting process:

“The National Electoral Committee notes, however, that just as the voters who arrived at the polling station before the time it is closed must be allowed to cast their vote, because the difficulty of the election organizer in organizing the work and the resulting delay must not lead to a situation where the voter does not vote. The voter must also be given the opportunity to vote when using the voter application to vote if he has authenticated in the electronic voting system before the time the voting ends (currently 04.03.2023 at 20:00).”

According to logs this is not the case since authentication was done at the same time vote was submitted, that is 20:13 (validity confirmation 20:13:24 without a previous authentication request), which was also admitted by SEO manager Arne Koitmäe on 15th of March in a comment to Õhtuleht:

“The case where, according to the log, identification took place at 20:13 p.m. is an exception,” Koitmäe explained, describing how the election service sees the case of voting after the official end of e-elections. “We were dealing with a voter who sent his vote to the e-ballot box not with an official, but with a self-made voter application. 20:13 is the moment his vote reached the e-ballot box. No personal identification took place and it would be correct to display a dash in that place in the log.”

Thus, the SEO also admits that it would have been correct not to include this container in ballot box, but according to all confirmations they did. As there precedent was made to create an ad hoc annulment list to remove presumably incorrect ballots, the same procedure could have been used to remove the container SEO itself considered null and void. It is not clear why this path was not pursued, because from explanations to media in March 15 it apprears that electoral authorities were well aware that this a vote submitted without any previous session and the comparison to voter already in polling station finishing the casting of a ballot is not correct.

During the 16th of March meeting it was chosen to use this inadequate comparison and instead of correctly counting my vote my motivation as an election observer was risen as a topic. NEC members from National Audit Office and Chancellor of Justice speculated about me being a hostile agent or playing tricks and suggested that the problem should not be considered from voter rights point of view. It was made clear to me that the decision to not count my proper vote and instead process the container that was not supposed to be included in ballot box is deliberate and not related to law of legal responsibilities of NEC, but their interpretation of me as a person.

The first part of the episode is only about failing to remove the vote cast at 20:13, when e-voting was over. But what would have happened, if this overtime container was removed from the ballot box? Actually the vote container was also processed incorrectly, because election software processes the containers in the wrong order. If the software followed the order indicated in Election Act, different process would have happened even without removing the vote cast after the end of electronic voting period.

Software counting votes in wrong order

).](https://gafgaf.infoaed.ee/images/votes4.png)

The container submitted to vote collection server at 20:13 contains encrypted ballot which consists only of 384 bytes and cannot be decrypted with official tools. Therefore it does not contain anything which could be called a vote according to the law, because according to NEC decision decision no 47 of 10.10.2022 defining vote format for 2023 parliamentary elections explicitly states that electronic vote is decrypted text consising of four fields.

The process described in § 487 of the Election Act requires counting of the last vote and therefore the processing should have moved back to previously submitted container to find a container with a vote to be counted. If we would move on to container submitted in session starting in 19:58, this also contains an encrypted ballot that consists of 384 bytes. In fact this is exactly the same container, but submitted just before the VOTING_END.

Following the law both of these containers should have been processed, but not finding a decryptable vote inside, they should have been omitted, moving back to last submitted vote, that SEO is able to decrypt. The previous vote was submitted 19:21 and contained an encrypted ballot which contains 797 bytes and could have been correctly decrypted by official vote processing software. This is arguably the vote to represent my choice in election, that SEO should have counted, but failed to do it because instead decided to not pursue the process described in law.

, presumably without noticing it creates a procedure that differs from the one specified in the Election Act.](https://gafgaf.infoaed.ee/images/recurrent.png)

At the NEC March 16th meeting Oliver Kask, the head of NEC, admitted that according to § 487 of the Election Act, last valid e-vote should indeed have been counted. Vote counting procedure diverging from § 487 of the Election Act in the vote counting software is also detectable, where the removal of duplicate votes (removeRecurrentVotes) is carried out before the containers and the votes contained in them are checked for formal correctness (removeInvalidCiphertexts). This way votes that are correct and that should be counted as last electronic vote of the voter may be mistakenly removed – which is what happened for this particular vote.

The container submitted 19:21 might have posed another challenge to SEO, because it recycled a container submitted earlier, but at least this could have been legally processed. According to § 487 of the Election Act the ballot from this container should have been taken to represent my vote at the election. In fact the vote submitted 19:21 might have been the only correct electronic vote in the elections, because compared to containers produced by official voting application it had a valid digital signature (see more on that in episode 4).

Private session to observe the containers

The first attempt to find out how my irregular votes were processed happened during the official vote counting procedures at 20:00 on March 5h Election Day. During the official procedures the contracted moderator Margo Loor explaining the processes claimed that one of the ballots was already removed from ballot box before the actual counting process because of “wrong encryption key” was used. It appeared that during 15:00 preparatory session already some of the votes were removed from the ballot box, despite the legal requirement that counting starts 20:00 when polling stations are closed.

As I had already learned from key generation procedures in eposode 1, the operator should not be disturbed during the processes and there had to be recount on the next day where all questions will be answered, I only tried to informally acquire more details from the moderator, who was not able to specify. However during the recount on March 6th it appeared that the procedures from 15:00 session on Election Day were not repeated. Asking how to observe the ballot procedures related to processing my experimental containers I was instructed to file a personal data request, which I did on the spot 12:12 on 6th of March.

I received a refusal to fullfill the request three days later March 9th 21:14, which left me with only couple of hours to file an official complaint on time. As there was an announcement in media about Conservative People’s Party (CPP) demanding a recount and SEO head Arne Koitmäe confirming this will be pursued, I approached both for the details and got a confirmation from CPP to include me in their delegation. The meeting with SEO and CPP happened on 10th of March, but was not really a recount, but rather a discussion.

I was provided with voting session logs by CPP, who had received these from SEO, which I analysed at the spot and claimed that based on inspection of the timestamps some of the containers I submitted to voting server are missing from the logs. Because of the heated atmosphere and as I brought this up at the very end of the meeting, I was suggested that SEO organises for me a private container inspecting session where we can unpack the ballot box and this way they will fulfill the personal data request about processing the containers, which they had refused from doing just less than 12 hours before.

I gladly received the offer and the condition for me was to not record any of the data that is shown to me, because otherwise I could prove who I voted for in the elections (more on that in episode 5).

During the session the ballot box file was copied to SEO laptop and containers submitted by me extracted. Together with SEO operator Indrek Leesi we counted altogether 26 containers in the ballot box and had a more precise look on the ones that were submitted before and after March 4th VOTING_END. We were able to confirm that indeed the containers submitted by voting application prototype during Match 4th were received and stored at the ballot box. CEO operator also confirmed that to his best knowledge the container submitted 20:13 was processed as my last vote and most probably discarded as an invalid ballot on 15:00 session of March 5th.

For me as an observer this session provided the proof that the last experimental containers submitted to voting server are stored in the ballot box and my own logs cohere with the ones of SEO. However, the session was very limited in nature and did not provide any opportunities to observe the actual ballot processing procedures. As counting vote submitted 20:13 was twofoldly problematic and there was reason to doubt that procedure during the informal 15:00 session on the Election Day was not following the provisions of the Election Act, I submitted an official complaint on March 13th, making sure to fit in three day deadline from the procedure.

During the session it also appeared that the digital signatures of containers submitted by official voting application were invalid also in ballot box as it was stored at SEO, because the Digidoc tool used to inspect the containers displayed “Signature is not valid” notice for the containers that were created by official application. Only the signatures of the containers created by my voting application prototype appeared to be correct.

For this episode the need to engage in a private vote counting session underlines the the problematic status of observing ballot procedures of electronic voting. First of all the Election Act explicitly states that “counting of votes cast by electronic means is public”, which clearly was not the case as I was explicitly forbidden to record or make notes of the process. But more specifically this shows that there is no meaningful dispute resolution mechanism in place, which makes SEO and NEC to engage in ad hoc decisions without legal prescriptions to regulate their assessments.

From procedural security point of view during this session for at least five minutes I was left alone in the SEO hall with the laptop that had full electronic ballot box stored on it, part of which was in the middle of being extracted in order to be inspected. I could have taken the laptop and just walked out the SEO premises, taking with me all the electronic votes that the SEO was protecting from me so dedicatedly, that I wasn’t even allowed to write down timestamps of vote containers submitted by myself – the containers which I actually had stored on my own computer during the casting of my electronic votes.

Legal proceedings

The Supreme Court, in the decision of the case 5-23-22 on March 30th rejected the corresponding appeal due to the exceeding of the appeal deadline and the fact that the appellant did not request the reinstatement of the deadline in the text of the complaing to NEC. This was a formal excuse, because the reinstatement of the deadline was requested at the NEC meeting, where the issue was discussed and reasoned based on delays from SEO and continuous process in finding out about the details relevant to assessing correctness of the ballot procedures. As the same was also explained in appeal to Supreme Court, there was no legal obstacle for reinstating the deadline.

Deliberately not counting a vote is criminal offence according to Penal Code §163 “incorrect counting of votes is punishable by a pecuniary punishment or up to three years’ imprisonment”. Although there was plenty of evidence that my vote was not counted from statements of SEO, source code of vote processing application and the containers submitted, neither Corruption Offences Bureau nor Prosecutor’s Office was ready to investigate the offence based on offence report 23221000023 about “incorrect counting of the votes” that was submitted on 26th of April, more than two weeks before the ballot box was supposedly physically destroyed by SEO on 12th of May.

Ingoring the obligation to count the vote of sole citizen might not cause a revolt and might be ignored even if legally wrong. However this episode is an example of how not defining precisely enough what exactly is an electronic vote and the exact legal process to count the votes will lead to problems. Aversion to invalid ballots and endeavor to keep the image of electronic voting flawless might have also played a part in ignoring this twofold issue, from which removing the vote submitted after the end of election could have been easy to solve as SEO was already engaging in practise of removing unwanted ballots from the ballot box.

As the reason given for not counting my vote was not argued legally, but based on contradicting comparisons and false statements about the actual process and also speculation about my motives as an observer and a voter, this left an unprofessional impression of SEO/NEC and their motives.

The irregularity of the procedures and lack of accountability motivated the observers to assess more critically the SEO/NEC statements about the rest of procedures.

The episode about efforts to observe and correct counting of individual ballots is the most detailed of the episodes, but would have had only negligible effect on the election outcome. The following two episodes concerning failure to process the rest of 312 181 electronic votes would have had major impact on the election results. From legal perspective the episodes could have been treated as one, but they appeared separately and missing EHAK codes of administrative units were addressed in a separate complaint by another observer, preceding my queries about the technical details. For that reason they are described as separate episodes of observation.

For observers both missing the EHAK codes as well as failure of digital signatures initially seemed rather minor technical glitches, legal implications of which started to emerge in discussions among observers and were underlined by reluctance of electoral bodies to provide details about irregularities and refraining from commenting, arguably also hiding relevant details from Supreme Court.

3. Absence of district code in the text of the e-vote

SEO illegally counted the electronic votes that did not specify the codes of administrative units (EHAK codes) required in point 3.3.1 of NEC decision no 47 of 10.10.2022 defining vote format for 2023 parliamentary elections. According to Election Act section 37 paragraph 1 NEC is required to specify the format and data fields of electronic vote, which decision no 47 rightfully did, defining the electronic ballot form consisting of four data fields:

3.3.1. administrative unit EHAK code and ASCII hexadecimal code 2E;

3.3.2. candidate's registration number and ASCII hexadecimal code 1F;

3.3.3. party name or individual candidates label and ASCII hexadecimal code 1F;

3.3.4. candidate's first and last name.

However, by downloading and inspecting vote containers with independent verification application it appeared that EHAK code is missing. Although initially refraining from comments in NEC decision no 84 of 5.04.2023 SEO finally confirms that e-votes indeed did not specify the proper EHAK code in vote text:

“The Riigikogu elections, the European Parliament elections and the referendum are all one election event. Therefore, the EHAK code is always

0000. In local elections, the code is different. The voting result is determined not by the municipality, but by the district. The association of the voter with a certain administrative unit when determining the voting result is therefore not necessary in Riigikogu elections.”

0000 for all votes submitted by official voting application. The actual code was recorded outside the container for reasons not disclosed.

In that SEO claims that for all e-votes in the 2023 Riigikogu elections in place of the EHAK code 0000 was recorded, but fails to explain why. SEO also misleads by claiming that EHAK classificators are not used in parliamentary elections. For example votes for Johanna-Maria Lehtme who ran in district no 1 the votes were registered to administrative units with codes 0176 (Haabersti), 0339 (Kristiine) and 0614 (Põhja-Tallinn), which are also used to categorise the vote counts in official electronic voting results.

The EHAK codes are established by ministerial regulation on the basis of §6 subsection 51 of the Territory of Estonia Administrative Division Act and start from the value 0001 (EHAK specification).

Electronic votes, which “do not conform to form decided by the Electoral Committee” should have been detected according to § 601 paragraph 6 of the Electoral Act. Therefore, electronic votes without the appropriate EHAK code should have been labelled as invalid ballots and not counted in the election result.

The Supreme Court also unequivocally confirms in point 27 of the decision in case 5-21-15 from 2021 that NEC with its decision establishes the format and data fields of e-vote, providing “decrypted electronic vote data elements (administrative unit code, candidate’s registration number, candidate’s first and last name)” and adds:

“If the electronic vote does not meet the mentioned requirements, it is invalid.”

According to the SEO, none of the 312,181 e-votes counted in the 2023 Riigikogu elections did meet the mentioned requirement, i.e. the e-vote data elements did not have any meaningful administrative unit codes on the decrypted data fields of electronic vote and instead had character sequence 0000 in place of EHAK code. All such votes should have been declared invalid during the tally.

Non-procedural cancellation list for votes in the wrong district

In relation to the handling of EHAK codes SEO decided to remove up to 63 vote containers presumably containing votes for a candidate from a wrong electoral district using a non-procedural cancellation list. The possibility for such an intervention was neither specified by the law nor were observers provided with opportunity to oversee the process.

The issues related to such removal were discussed by the Supreme Court in the case 5-23-11, but apparently in paragraphs 31-34 of the resolution the court was not informed that EHAK codes were always 0000 in the decrypted data fields of the e-votes. Therefore, the explanations of the Supreme Court are erroneous as they claim:

“Electronic votes that meet the conditions set out in § 601 section 6 of the Electoral Act and need to be declared invalid, are determined in the vote counting phase, after their anonymization (separation of the electronic vote from the container containing personal data) and opening (decryption). If the vote decryption result is not among the candidates running in that district, the vote is declared invalid. This is done by checking the correspondence between the administrative code of the electoral district and the candidate’s registration number included in the electronic vote. This process is monitored by an auditor, and the proof of decryption allows the mathematical correctness of the process to be checked using the audit application. Therefore, opening the vote of a particular voter in order to make sure whether the vote was cast for a candidate of the wrong electoral district in violation of Section 601 section 6 of the Election Act was not necessary.”

The Supreme Court correcly explains that in order to declare a vote invalid, ballot ciphertexts should be anonymised and decrypted, but then goes on to simply claim that in current case the procedure just explained “was not necessary”. They fail to give explanation on how there can be other ways to declare a vote given to candidate in wrong discrict invalid besides decrypting the vote and looking up the EHAK code in the ciphertext.

In the procedures conducted this was in fact possible because the vote containers were internally stored according to the electoral district, that was separately recorded outside the container. So it is true that if the procedure described in Election Act would have been followed, the ballots would have been declared invalid as the Supreme Court indicates, but not only because of containing EHAK code of the wrong district as the resolution explains, but because the code was set to 0000 for all electronic ballots.

This crucial link in the chain of the argumentation that would be needed to explain why it was not necessary to decrypt the ballots is conspicuously missing in Supreme Court resolution and the last sentence quoted starting with therefore is completely unfounded.

The reason for that missing link can be either not being informed about the process and the need for decryption in order to declare a ballot given for a candidate from a wrong disctrict invalid or that they were indeed informed that the actual ballots in election did not conform to NEC decision no 47 of 10.10.2022, containing 0000 instead of valid EHAK code, but for some reason did not want to include that in the resolution.

As the containers were declared invalid and removed before anonymisation and decryption, the claims of Supreme Court do not describe the process as it actually happened leaving out substantial part of it and were either mislead by the NEC/SEO or in cooperation with the electoral authorities were trying to misead the public themselves.

If the resulting three votes from the four containers were processed correctly, most probably those votes would have been counted as invalid ballots after decryption, if the district of the vote containers was internally stored correctly and checked after anonymisation and mixing. If this were not the case, there could be also other votes intentionally submitted for the wrong district in elections, that were counted without detecting the manipulation.

SEO/NEC did not sufficiently explain why they decided to create a non-procedural cancellation list, which should not have been needed to declare the ballots invalid.

One could presume that they either did not want invalid ballots to end up in election statistics or were not sure if the software is able to process the containters correctly, not allowing to cast a vote for a candidate of a wrong district in the final tally.

Although it is highly probable that those containers did contain invalid ballots, this was not proven according to the law, which according to § 601 sections 4 and 6 of the Election Act requires decrypting the ciphertext to declare a ballot invalid. If the goal was to not allow invalid ballots to show up in the results, this could be considered as an attempt to manipulate election statistics. If the goal was to avoid error, that would have happened in later phase of processing the votes, this should have explained as such and dealt with after it actually happened.

If the error was detected in advance, but the public and the Supreme Court was not informed about it, this would cast a serious doubt on integrity of the electoral bodies themselves.

4. Invalid digital signatures of e-vote containers

The problem of digital signatures appeared first as a peculiarity of how official voting application manages certificate validity checks. For most of the government services validity of a certicicate used for signing the documents is checked using to Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) during the creation of an actual signature container. Discussions among the observers and SEO officials initially focused on reasons for unconventional order of the certificate validation procedures, but did not focus on the fact that singatures are flagged invalid by official Digidoc utility.

However the question was raised on 21st of March as part of election complaint no 78 by Meelis Kaldalu and Supreme Court case 5-23-24, where the authorities failed to comment on the issue. The apellant referred to sample ballots downloaded by Kryptogramm, that were published as example data for vote verification application. As an observer I submitted a question about irregularities related to EHAK codes and invalid digital signatures by e-mail on March 28th in reply to refusals to provide me with terminal logs of vote processing sessions about my personal votes as described in episode 2. The question was answered another week later on April 4th after filing an official complaint on 30th of March.

In processing the complaint it appeared that SEO counted the e-votes that did not have the digital signatures required in point 3.1 of §484 subsection 4 of the Election Act and NEC decision no 47 of 10.10.2022. In this matter as with EHAK codes, the SEO/NEC does not refute the fact of the invalidity of the digital signatures of the e-vote containers that were downloaded and inspected. In the decision no 84 of 5.04.2023 SEO rather goes on to speculate that there cannot be invalid digial signatures per se:

“A digital signature cannot be invalid, a signature is always valid, just like a person’s physical signature. A certificate can be invalid, and in this case a document with a valid signature, which was not valid at the time the certificates were issued - the signed document is not valid. Digital signatures are not invalid, because digital signatures are given with an ID card or Mobile-ID, and the confirmation of the validity of the certificates is in the ballot box together with the vote.”

invalid.](https://gafgaf.infoaed.ee/images/invalids.png)

A closer look reveals that the official Digidoc application declares the signatures of vote containers invalid (displaying a red warning letter “Signature is not valid” and declaring: “This is an invalid signature or malformed digitally signed file. The signature is not valid.”) because the containers created do not comply with container format requirements. The error report in “Technical information” textarea complains about missing a required UnsignedProperties element:

“SignatureXAdES_LTA.cpp:203 Signature validation

SignatureXAdES_T.cpp:226 QualifyingProperties block ‘UnsignedProperties’ is missing.”

According to Election Act § 484 paragraph 4, e-votes must be equipped with “a digital signature in accordance with the requirements of the e-identification and e-transactions trust services act” and according to section 3.1 of NEC decision no. 47 of 10.10.2022 “an electronically signed electronic vote is a file in ASiC-E LT format”. The ASiC-E LT requirements for Estonian digital signatures are described in BDOC specification and according to BDOC 2.1 it is mandatory to define UnsignedProperties element in QualifyingProperties block of the container.

E-vote containers produced by official voter application do not meet the requirements of the BDOC 2.1 format, apparently also not meeting the requirements of § 24 section 1 of the Electronic Identification and Trust Services for Electronic Transactions Act. Those containers should have been declared corrupt when processed according to § 601 paragraph 6 of the Election Act, because they “do not conform to the format established by the NEC”, and votes enclosed in such containers to be counted as invalid, but this was not done.

NEC and SEO did not refute that in addition to the invalid digital signatures detected in sample containers the rest of digital signatures of all 312 181 e-vote containers were invalid too. Since the digital media containing the electronic votes was destroyed in May 12th, there are no final proofs about this except the proofs that can be derived from reverse engineering of the official voting application.

Similar to the absence of EHAK codes, SEO did not refute the invalidity of digital signatures in e-vote containers, but justified the non-compliance with the requirements by stating that “validity confirmation of the certificates is located in the ballot box together with the vote” – which is not allowed by requirements of an elecronic vote established by the NEC, according to which the digitally signed e-vote is a file in ASiC‑E LT format. Therefore, it must be concluded that the SEO has incorrectly counted the votes, including e-votes from containers with incorrect digital signatures.

In the decision of the case 5-23-26 on April 20, 2023, the Supreme Court left the appeal regarding EHAK codes and digital signatures unreviewed, as the appeal deadline had passed. Reinstatement of the deadline was requested and was explained by SEO/NEC refusing to provide comments for investigating the issue, arguably NEC announcing the elecion results without processing this complaint was also against the law as according to Election Act § 74 they are allowed to declare the results “if final resolutions or judgments have been adopted in respect of the complaints filed” (more on that in episode 6).

5. Failure to provide secret ballot

The problem with ballot secrecy in IVXV protocol was already well known issue, that was discussed in ministerial working group to improve e-voting in 2019. According to official explanation voter should not be able to obtain strong proof of who they voted for:

“Note, however, that the voter cannot obtain a strong proof that her vote was included in the final tally as such a proof could potentially be used for vote selling.”

Yet already OSCE/ODIHR observation mission stated in 2019:

“A review of operational and technical frameworks by the ODIHR EET indicates that an internal attacker with privileged access to digital ballots could break the vote secrecy of any voter who published an image of the QR code online, even after the expiry of the code’s validity. This contradicts national legislation and international standards pertaining to vote secrecy.”

SEO and NEC have dismisseed concerns about vote privacy in their comments and during this election it was demonstrated by using the independent vote verification tool and actual data requests to authorities, that voters can obtain digitally signed proof of their choice in elecitons. The expert report about this possibility was also part of election complaint by CPP, that was dismissed by Supreme Court in case 5-23-20 without discussing the content, but with the Chief Justice suggesting constitutional review concerning the responsibilities of electoral bodies.

In current implementation of the voting procedure the voting application creates a digitally signed container with a cryptogram of voter choice, encrypted using ElGamal algorithm by SEO/NEC public key and ephemeral key as required by the encryption algorithm (see general description in the introduction).

The container is sumbitted to vote collection server by the voting application and voter is provided with a possibility to make sure server has received and stored the container. Vote verification is implemented by displaying to voter a QR code, which contains the ephemeral key and vote identification number and is supposed to be scanned and decoded by a separate device, in official implementation a smartphone. The original digitally signed vote cryptogram is then downloaded by independent device from vote collection server by providing vote identification number and decrypted using SEO/NEC public key and the ephemeral key forwarded in the QR code.

As a result voter is displayed the candidate name and number from the actual cryptogram, which will be later decrypted by SEO/NEC private key and counted.

Already displaying the actual choice in election to a voter provides means to disclose the voter choice to third parties either intentionally or unintentionally. In order to make this legally acceptable, the constitutional principle of secret ballot has been reinterpreted as a responsibility of a voter instead of election managers, who have to provide privacy for voter during writing the candidate numbers on ballot, preferrably in a special voting booth behind a curtain.

This reinterpretation of ballot secrecy is quite natural as there is no way to guarantee voting privacy in uncontrolled environments like homes, offices, cafés and similar. However, the presumption of voter not being able to provide strong proofs of choice in election has remained.

According to official documentation the possibility to provide strong proof of voter choice is mitigated by allowing voters to recast their votes. Yet the current technical implementation of the protocol also allows voter to receive full list of timestamps and receipts of electronic votes given in election. These can be used to prove to third parties, which one of the electronic votes was the last vote that was actually counted.

This goes much further than just enabling voting in uncontrolled environments and from technical perspective is a side effect of using digital ID to cast the votes.

Casting of an electronic vote requires using EIDAS compliant digital identity, which means that the validity of certificate used for signature has to be checked during casting the vote. Validity checks are logged at the servers of certification authority and these logs can be obtained either by logging in to public MyID service of the local certification authority SK ID Solutions and downloading the logs in convenient format or making a personal data query to certification authority.

In this way voter can prove which of the electronic votes was the last one cast by the voter. The fact that revoting is available does not help to weaken the proof obtained, because with OCSP logs from SK solutions voters can prove that they did not recast their particular vote. In addition according to Election Act § 23 the list of voters is public and voters can obtain proof if they voted electronically or by using paper ballot. This proof is provided upon personal data request to SEO.

Combining digitally signed e-vote cryptogram, certification authority logs and response to SEO query voters can obtain strong proof of their final choice in election. Despite the exact procedure of obtaining such proof was demonstrated during elections, SEO went on to deny such possibility in media. NEC and Supreme Court failed to address the issue, NEC explaining that their responsibility according to Election Act §9 to “exercise supervision over the activities of the elections managers” does not include assessing SEO statements about election protocols in media, even if the statements are misleading or deliberately making false claims about the electronic voting protocol.

As avoiding to let voters prove who they voted is recurring motive for SEO/NEC in explaining why observing the ballot procedures can not be allowed or how end-to-end verifiability suggested by OSCE/ODIHR could enable vote buying, the fact that current protocol in fact provides voter with a possibility to obtain hard proof about the choice in elections is another example that adds to legal make-believe that is required to keep electronic voting happening in Estonia.

6. Ascertaining the results using ad hoc procedures

Missing EHAK codes and invalid digital signatures were detected by downloading of the vote containers produced by official voter application and engaging in close inspection of the IVXV protocol with the independent vote verification application. The failure to process the containers in right order and remove a container submitted after election was over was also enabled by downloading the submitted containers and keeping track of them at the voter end of the system.

There was hardly any way for observers to oversee container processing events on the server side, but it was not possible to oversee processing of the vote containers on Election Day and during the public procedures on following day. How attempts to observe ballot procedures led to social engineering SEO to hold a private vote counting session was already documented as part of episode 2 of the report. The current episode puts the procedures in a broader context and discusses if and how the problems could have been fixed if procedures described in Election Act would have been followed.

Critical procedures conducted in informal session

According to § 601 paragraph 1 of the Electoral Act counting of the electonic votes starts after 20:00 in the Election Day, but the first session of the procedures started 15:00, when polling stations were in the middle of collecting paper ballots. According to KPMG’s 13.03.2023 interim report this first session that is not defined in Election Act included removing repeated votes and invalid containers, which are processes that directly affect the election results and could have only started 20:00.

The report does not disclose who were present at this informal session and SEO/NEC has refused to provide any details about what were the exact commands of the eleven step list from handbook of electronic voting chapter 3.1, that were executed and what was the resulting terminal output. The signatories of the petition to make e-voting observable reported that this session was not fully accessible to them, because of low quality of the video conference, but many of them did not even participate, because Election Act does not allow any of the procedures that could affect the ascertaining the election result to take place before polling stations have closed.

Yet these were the procedures that supposedly took care of the annulment lists and resulted in removing the invalid vote as reported by KPMG auditors. This is also the only time when integrity of the votes were checked, failing to detect invalid signatures of the containers submitted by the official voting application. According to OSCE/ODIHR 2023. report “the critical step of removing the votes overwritten by another vote cast on the internet or in a polling station was not audited” and as repeatedly recommended since 2011 “election authorities should consider methods to achieve end-to-end verifiability”.

Since the deficiencies of EHAK codes and digital signatures were not detected by vote processing software, this raises a question of the overall quality of those checks and what other irregularities in vote containers or what maniplulations could have passed unnoticed. Lack of proper checks by vote processing software is even more serious concern than voter application producing invalid containers, because weakness of vote processing software can be directly used to manipulate the election result.

The observers and the public were informed that during the next day from the Election Day there will be second counting of the votes, where all the procedures are repeated to make sure election result was ascertained correctly. According to KPMG’s 13.03.2023 interim report the second tally on 6.03 was only conducted partially and did not include all the procedures conducted on first session of 5.03 that started 15:00. Although election authorities replying to public criticisms suggested that even the third count might take place to address the concerns voiced by observers and political parties, this did not happen.

In fact, even the part of the first counting of the votes was done during informal session not foreseen by Election Act. As the procedures were only partially repeated on second day and the informal procedures were not repeated, the substantial part of ascertaining the election result happend without scrutiny of the observers. This makes it even more incriminating that the observers were not provided video or terminal logs of those informal sessions, although SEO/NEC implicated during observer orientation that either of those will be shared with the observers afterwards.

Failure to correct problems in legal recourse

According to the Election Act §74 NEC is only allowed to declare the election results “if final resolutions or judgments have been adopted in respect of the complaints filed”. In addition to dismissing the complaints because of deadlines or contesting rights, concerning complaint about missing EHAK codes and invalid digital signatures NEC failed to wait for the related resolution or judgement.

The question about how NEC explains invalid signatures was submitted as early as 21st of March, but was left unanswered in resolution on 23rd of Match and in Supreme Court judgement in case 5-23-24 from 30th of March. In Supreme Court judgement in case 5-23-11 about non-procedural annulment lists on 27th of March it appeared that in 31-33 the court is misinformed about the actual content of EHAK codes on electronic ballot texts.

The issue about EHAK codes and invalid signatures was actively discussed between the observers after 27th of March judgement, which made me as an observer formulate is a reqest for clarification to SEO/NEC on March 28th. Without getting an answer from SEO/NEC in two days and after Supreme Court judgement on 30th of March ignoring the issue of invalid digital signatures I resubmitted it as a formal election complaint on 30th of March.

On 30th of March NEC had its meeting where they informally discussed my complaint. From the protocol of meeting no 64 one can read that my complaint was introduced “before the immediate start of the meeting” and that NEC “had a discussion on the topic of the complaint, contesting rights, deadlines and announcement of the election results and found that complaint submitted is not an obstacle for announcing the election results”.

They also refer to Supreme Court judgement in case 5-21-31 from 2021 in as basis for that assessment. However the judgement in paragraph 21 referred explicitly states that the goal of the restriction for announcing the results before the final resolutions or judgements is to avoid the situation where after the elected body convenes “in processing of the complaints emerges a violation, which could affect voting or election result”.